Against all odds, Frank Herbert’s 1965 science fiction novel Dune has been adapted to the screen three times, though with varying degrees of faithfulness. David Lynch’s penchant for the grotesque shines through in his 1984 film Dune. John Harrison takes a Shakespearean approach in his 2000 television miniseries Frank Herbert’s Dune. Most recently, Denis Villeneuve showcases the visual beauty of the desert in his 2021 film Dune: Part One.

Although many things have changed in the political, social, and cultural landscape since the 1960s, Herbert’s book remains the same. So, directors, producers, and other cast and crew have had to make numerous decisions about how to adapt this story to their time period and audience. What they choose to keep, remove, or change impacts how true their adaptation is to the original novel. Even though all of these directors said publicly that they wanted to stay faithful to the source material, ultimately each had to make a choice about how strongly to hold to this conviction.

Here are a few of the features in each adaptation that either succeed in staying faithful or miss the mark.

Dune (1984)

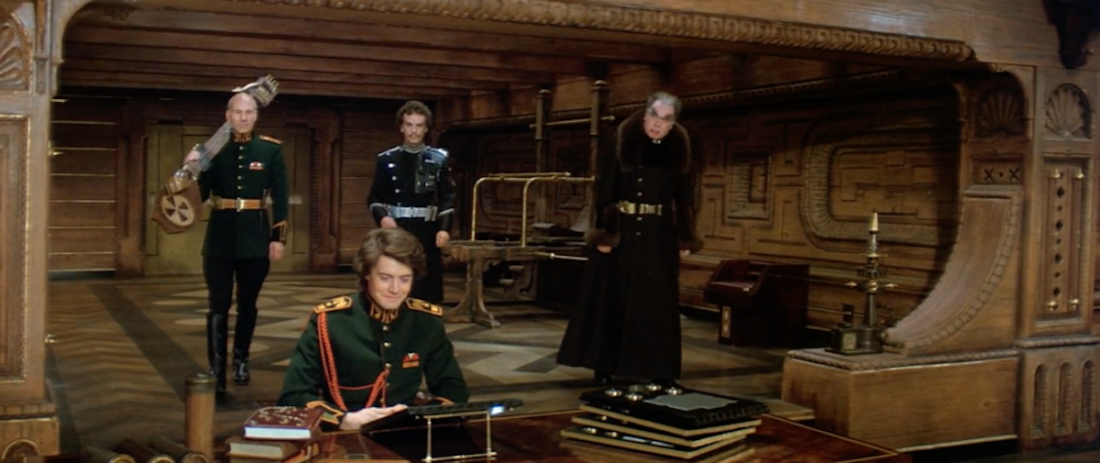

The script for Dune (1984) includes many lines taken directly from the book, especially in the first half of the film. In an early scene where Paul Atreides’ trusted teachers Thufir Hawat, Gurney Halleck, and Dr. Yueh enter a room with Paul sitting at a desk, the conversation is almost identical:

PAUL: I know, Thufir. I’m sitting with my back to the door. I heard you, Dr. Yueh, and Gurney coming down the hall.

THUFIR: Those sounds could be imitated.

PAUL: I’d know the difference.

There are many other examples of lines recognizable from the book in Lynch’s Dune. Herbert himself noted that he could hear his dialogue all the way through the movie and thought fans would enjoy tracking down the lines after watching it. Interestingly, one iconic line that isn’t in the book is “the spice must flow,” though this phrase from the film still accurately captures the strong desire for spice that drives the various factions in the Imperium.

Lynch’s Dune remains the only adaptation that attempts to stay faithful to the book’s inner monologues by including voice-overs. Throughout the film, the camera will hold steady on an actor’s face as they pause silently and a voice-over reveals what they are thinking in that moment. For example, after the conversation between Thufir and Paul mentioned above, the camera lingers on Thufir’s face as his voice-over says, “Yes, perhaps he would at that.” This line reflects Thufir’s inner thought from the book and clues the audience in to the idea that Paul has special perceptive abilities and little reason to worry about his personal safety. Later, after Jessica shows a hint of concern for Paul before he is left alone with the Reverend Mother Mohiam, Paul’s voice-over asks, “What does she fear?” Not only does this build suspense for the following scene with the gom jabbar test, it helps the audience understand Paul’s thought patterns. The voice-overs align with the book by letting viewers get inside the characters’ heads and experience events alongside them.

However, Lynch also took liberties with the source material that move his film further from the themes and concepts important to Herbert’s story. The weirding modules are one of the biggest changes. In the book, the Atreides’ advantage in combat lies with their strong training by fighters such as Duncan Idaho and Gurney Halleck. Paul has an additional advantage because he was trained in the supreme control of mind and body by his mother, a member of the Bene Gesserit Sisterhood. But in the film, weirding modules are introduced as the Atreides’ secret advantage. They take the name of the Bene Gesserit’s ‘weirding way’ and appear to work by harnessing the power of sound, but these point-and-shoot weapons require no skill to use. In his book A Masterpiece in Disarray: David Lynch’s Dune. An Oral History (2023), Max Evry suggests that they reflect Lynch’s interest in Transcendental Meditation and the power that one word or mantra can access. This may be true, but ironically the modules undercut the mental and physical strength and skill of both the Fremen warriors and the Bene Gesserit from the book. They unnecessarily add technological gadgets to a story that originally uplifted humans’ abilities over technology.

Frank Herbert’s Dune (2000)

Harrison’s miniseries Frank Herbert’s Dune takes special pains to explore the political and religious themes from the book and depict the Fremen as a multi-faceted desert people. The miniseries focuses on the political intrigue between the various factions of House Atreides, House Harkonnen, the Imperial household, and the Guild and Bene Gesserit. In a Shakespearean-influenced style, characters frequently reveal their political motives and schemes, including at the banquet on Arrakis. The Emperor and Princess Irulan also take on bigger roles, though largely in keeping with their descriptions from the book.

Religious influence plays a significant role in the story, as Paul and Jessica use myths and propaganda to their advantage in order to secure their place among the Fremen. Yet the Fremen are shown to be a strong and culturally vibrant desert people with their own traditions and rituals, even though they remain susceptible to Paul’s charisma. Harrison went so far as to hire a choreographer to design the hand gestures and body movements of the Fremen to bring their culture to life on screen. For example, Stilgar shows his respect for his crysknife by bringing it up to his forehead in a ritualistic motion before lowering it. Other Fremen bow their heads and make particular hand motions in the presence of Reverend Mother Ramallo and later Paul, which indicate their deference to religious figures. Such features provide depth to the Fremen culture, while staying firmly grounded in some of their characteristics from the book.

One notable deviation in the miniseries is when Paul appears to summon forth a waterfall in the Fremen sietch after proclaiming his right to reclaim his dukedom and cleanse the planet of their enemies. This scene, similar to the one at the end of Lynch’s film when Paul makes it rain, risks making Paul look like a god who can control the elements. Its purpose was likely to reinforce the religious nature of Paul’s leadership and the Fremen’s view of him as a messiah figure who can perform miracles. Water is certainly an important symbol, but it does not appear in this way in the original story.

Dune: Part One (2021)

Villeneuve’s Dune: Part One brings to life the hostile but stunning desert environment in the book through the use of on-location filming in the Middle East (specifically near Abu Dhabi and Wadi Rum in southern Jordan). This gives it the advantage of being able to show off the austere beauty of the desert and its rocks and sand dunes, as is appropriate for a story set on a desert planet. The wide vistas of rolling dunes and intense sunlight highlight the moisture-starved environment described in the book. Spice appears as a glittering substance in the air and on the ground, much prized and fought over by multiple groups.

The film also stays true to a smaller detail relating to the desert setting: how to walk in a non-rhythmic way to avoid attracting the attention of a giant sandworm. A choreographer created a special desert sandwalk that Jessica and Paul use when forced out on into the desert after the Harkonnen attack. In the film, as they venture out into the open sand in their stillsuits, Paul tells Jessica they must walk like the Fremen do—a practice he learned about in his filmbooks. He shows her how to do the sandwalk, taking a wide step with his right leg, a wide step with his left leg, and then a small step forward before making a sweeping circular motion with his left leg dragging through the sand. The depiction of this movement keeps the film true to the book’s descriptions of how people have learned to survive in the deserts of Arrakis.

On the other hand, perhaps in an attempt to avoid the excesses of the depiction of the Baron Harkonnen in Lynch’s film, Dune: Part One changes this character into a bald monster with few lines. Such a drastic shift neutralizes the Baron’s crafty, Machiavellian nature from the book and leans into a more stereotypical views of villains as barely human and animalistic. It makes it impossible to view the Harkonnen and Atreides as mirror images of one another, each manipulating those around them to obtain power and wealth. The loss of this interesting, articulate character from the book reduces the story’s political depth and the audience’s ability to enjoy watching his plots unfold and ultimately unravel.

Comparing Adaptations

In terms of how the adaptations compare with each other, all three have a few things in common in their approach to translating Herbert’s story to the screen.

First, all of them feature a female narrator providing a prologue to the story, whether Princess Irulan in Dune (1984) and Frank Herbert’s Dune, or Chani in Dune: Part One. For the first two adaptations, this aligns with Irulan introducing Paul through the excerpt from her writing that begins the book. Yet all of the adaptations then change the start of the main storyline where Reverend Mother Mohiam and Jessica look in on Paul the night before the test of the gom jabbar. After a second short prologue titled “A Secret Report Within The Guild,” Dune (1984) begins with the Emperor meeting the Guild and planning to kill Paul. The miniseries opens with a sequence of Paul’s visions and Paul waking up in his room with a hologram of Dr. Yueh lecturing about the political structures of the Imperium, though this scene is then immediately followed by the gom jabbar test. In Dune: Part One, after Chani’s prologue featuring scenes of spice in the air, spice harvesting operations, and the Fremen and Harkonnen conflict, Paul awakes on Caladan after having had visions of Chani and proceeds to have breakfast with his mother.

The adaptations often take quite different approaches to characters, sets, and costumes, giving them a unique look and feel that may be only loosely tied to the book. However, they all decided to go with an adult actor for Paul. In the book, Paul is 15 years old at the start and described as small for his age. Of the three lead actors, Timothée Chalamet is really the only one youthful-looking enough to pull this off—Kyle MacLachlan and Alec Newman look older than a young teenager. All the adaptations also include some effort to capture the blue color in the eyes of the Fremen through different special effects through the years, from rotoscoping to UV contact lenses to CGI-enabled blue tinting.

In addition, the later adaptations pay homage to their predecessor, Lynch’s Dune, even though they largely try to avoid replicating its specific look and feel. In the miniseries, Paul speaks the line “the sleeper has awakened” while discussing his terrible purpose with his mother. This is identical to the line that Paul utters after taking the Water of Life in Lynch’s version. Both the miniseries and Dune: Part One include a large Guild ship with a long, tubular structure reminiscent of the ship in Dune (1984). Herbert’s book doesn’t include details about these ships, other than the fact that they are very big but that sandworms could be larger, so the consistency of the ships’ appearances on screen indicates that the later adaptations are riffing off of the Lynch version’s ship design.

Villeneuve’s film also contains several other similarities to Lynch’s film. There is a Soviet influence in the Harkonnen ships and architecture and marks on the Mentats’ lips. The Baron Harkonnen bathes in a dark, industrial-looking substance (also recalling a scene from the film Apocalypse Now). There is also a hint of Lynch’s strange preoccupation with animals, which popped up in Dune (1984) numerous times through the Harkonnens’ mutilated cow, cat/rat antidote set-up, and squood device. In Dune: Part One, a weird spider-like creature appears eating out of a bowl on the floor in the Harkonnen chambers and is dismissed in disgust by Reverend Mother Mohiam. With no explanation or backstory, it appears to be another way of demonstrating the Harkonnens’ animalistic nature and monstrosity, similar to how the creatures function in Lynch’s film.

Conclusion

Herbert’s long, multi-layered book has posed many challenges to those who have attempted to adapt it to the screen. Herbert himself couldn’t write a workable screenplay and concluded that he was probably too close to the material to see it as a film. But three directors and their teams have navigated some of the complexities of Herbert’s story successfully enough to bring a screen adaptation to life. Each expressed a desire to be faithful to the source material but also had to try to align their vision with the realities of their time period and the constraints of cinematic production. Some aspects of the resulting films are more faithful than others, leaving plenty of room for discussion and debate about how the adaptations stand up against the original, unchanging novel.

So, let’s discuss: Which adaptation do you think was most faithful to the spirit of the book? Are there features you found that aligned closely to Herbert’s vision, or perhaps other features that exist only in the cinematic versions that have remained in your mind? And do you think the new film, Dune: Part Two, will stay more or less faithful to the novel than Part One?

It’s been a while since I read the 2 sequels, but I think the description of the Guide ships comes from there.

Nothing can make me forget Kyle having a knife fight with metal mankini-clad Sting.

Of course Sting was wearing the famous winged underpants when he came out of the shower but when it came to the fight with Paul he was fully dressed in Harkonnen blue flexi-armour stuff.

“Metal mankini-clad Sting” I’ll be in my bunk

I really enjoyed the SciFi miniseries the most (and the sequel miniseries is nearly perfect, considering the source material). You really need the multiple hours to get everything in there, or you end up (as you pointed out with the latest version) neutering the story.

I was even more impressed with the sequel, Children of Dune, than the original Dune mini-series. It is an overlooked part of the story that brings out Paul’s fear of his fate and his son Leto’s decision to make the sacrifice to “return to the sand”.

OP: “The sleeper has awakened” is from the book, not just the Lynch film.

There are definitely choices that have to made to adapt any written work… characters, subplots, and world-building all get sacrificed to one degree or another. So far I think the miniseries has had the most faithful adaptation to the story. But the new movies have been the closest to truly depicting the scale of everything in the Dune universe, and certainly is the most visually beautiful.

I was NOT aware of the TV series. Is it available somewhere?

It is available in DVD from Amazon.

Also I found all episodes on Youtube

I was lucky enough to see Dune: Part Two Sunday evening, and I was blown away. I think that DV’s versions are probably closest to the book. It was incredible to see how much of the second half of the novel was included.

The ending is slightly different, but the big story beats remain the same. The scenes including the Water of Life were really mesmerizing and struck a good balance between the mysticism and “science-fiction” of it all.

There is also much more religion in Part Two, and you really understand the impact that both the Fremen beliefs and the Bene Gesseritt propaganda has on this planet as they suddenly find themselves confronted with the idea that their Messiah has arrived.

I saw part 2 as well and really, really enjoyed it. However, I might be in the minority here, but I feel that Chalamet and Zendaya’s total lack of chemistry as Paul and Chani is one of the big bummers of the film. I didn’t really get the feeling of connection that is present in to books from their performance. Still, the film is incredible and does a very good job of staying faithful to the source material.

I’ve only read the book and seen Dune: Part I, but while I appreciated the epic scale with which the film treats the material, I disliked the portrayal of the battle between the forces of the Baron and those of the Duke. One of the distinguishing factors of Herbert’s worldbuilding is how no one uses laser weapons anymore due to the catastrophic consequences of a laser interacting with a shield. In the battle scenes, we see lasers aplenty. More generally, the movie portrays the battle as an inevitable Harkonnen win, bringing an absolute crushing force against the unsuspecting Atreides. In the book, while they certainly lose, they are at least portrayed as having a chance. It’s more of a tragic loss, with honor (Duke Leto even manages to kill Piter and severely injure the Baron). In the film the situation is portrayed as so hopeless it’s not even a tragedy – it’s just a “doompocolypse.”

In the book we do see lasguns aplenty. On Arrakis no-one uses shields much because they drive the worms into a frenzy. Harkonnen agents were caught trying to smuggle lasguns onto Arrakis in the early chapters leading to worries about assassination by lasgun-shield explosion and several Harkonnen troops are mentioned as carrying the weapons.

During the battle, when he sees that the Harkonnen/Sardaukar forces are using lasguns in their pursuit of Paul and Jessica, Duncan Idaho plants shields in the sands to eliminate the pusuers and cover their escape.

So I’m fine with the use of lasers in it.

For the Lynch film, it has Brad Dourif, who is good in anything.

For the miniseries, Ian McNiece by far proved to be the best Baron Harkonnen.

For the new film, they have the best ornithopters.

It’s been a while since I saw the miniseries, but I remember it being very faithful to the story. It may be the closest in simply sticking to the narrative.

But Villeneuve shows the best understanding of what Frank Herbert was actually trying to say with the Dune books. His Paul has character traits that suggest Villeneuve actually read the sequels (which I understand he has) and knows where it’s going. All in all, Villeneuve’s is my favorite adaptation so far.

Lynch’s version looks cool, but he really didn’t get what it was all about.

RIP Jodorowsky’s Dune.

I did enjoy the Lynch film, and like some of the additions, though I dislike others. I remember being disappointed with the mini series, primarily because I thought that with so much extra time there would be more material included, but I haven’t seen it on so long I can’t remember any specifics. I definitely feel the most recent Part One is the most faithful to the book; I re-read Dune before seeing the film because I wanted to be able to separate what was actually in the book versus what was added in previous adaptations.

In addition to his genes, Paul learned leadership from his father, politics & body control from his mother, fighting from Duncan & Gurney, knowledge from Dr. Yueh, and logic & its predictive nature from Thufir. Dune pt. 1 is beautiful, but you’d never know what a mentat is or really why the stakes on Dune were so large for the entire universe (Guild, Great Houses, Bene Gesserit, Emperor, Mentats, Fremen, etc.) We need to rely on the books to fill in all the gaps.

I suspect the reason the look of the first series appears to have had such an influence on the re-makes is not because of Lynch per se, but because the design work was done by Chris Foss and H.R. Giger, whose design work, along with similar people’s work, like Ron Cobb (Alien, obviously also with Giger), have had a huge influence on all modern SF films, not just the Dune re-makes.

In all honesty the Lynch version has been one of my favorite movies. I always hated the ending, it was trying to rush storyline and bring everything to a clean close. There is a version of the film that is narrated by the Emperor, which was a little more in depth, but still had the rush at the end.

The Syfy miniseries was ok but also reminded me of a really long school play.

Dune part 1 was great! I eagerly look forward to part 2.

The miniseries are perhaps the most faithful adaptations of the novels and I really enjoyed them as a book. The new films are a gorgeous retelling of the story, but with significant deviations that work really well, and I enjoyed them as a fan of stories well told.

I had high hopes for Dune 2, and while it delivered visually and hit most of the main plot points, it failed wildly in its characterization of Stilgar, Jessica, and the Paul-Chani relationship. I suspect most of that is due to the decision to compress roughly six years of the book into six months or so. I don’t even know how in the hell DV is going to make Dune 3/Messiah/Children with the way he chose to end part 2.

Ultimately the SciFi Channel miniseries are far and away the most faithful film adaptation of the books.

A long time since I read the book, but I seem to remember Paul being a more tragic figure. Past a point, his prescience mostly tells him there is nothing he can do to STOP the jihad. His position is akin to a man who starts a fire to avoid freezing to death, then realises it’s out of control and will burn three towns down to the ground.

The sci-fi channel dune miniseries were always my favorite. Alec Newman’s portrayal of Paul Atreides is perfect.

Glad you included the TV mini series into this article. I think that version has an incredibly strong perspective towards the politics and complexities of world building, understanding the complexity between houses ect. In context I think its the biggest thing the 1984 and Dune 1 & 2 lack. That particular version doesn’t get which credit for what it was and able to do and even had a great followup with Children of Dune.

I haven’t seen the TV series but I’ve heard it’s very good and has the best version of Baron Harkonnen.

I’ve seen Dune 1984 and Dune Part One, and there are a couple of things the older film did better, in my opinion.

For one, Dune 1984 doesn’t just tell us the spice is important, it shows us…by showing the Spacing Guild transport the entire Atreides household to Arrakis. That scene really helps us the audience grasp how vital the spice is to this interstellar empire’s travel and commerce. We also see their political power in the scene where the guild Navigator meets with the Emperor.

Second, Dune 1984 sold Dr Yueh’s betrayal of the Atreides much better. Yuen is barely in the newer film, while in Dune 1984 you really see his closeness with the family and his importance as one of Paul’s teachers. It makes his betrayal so much more harsh.